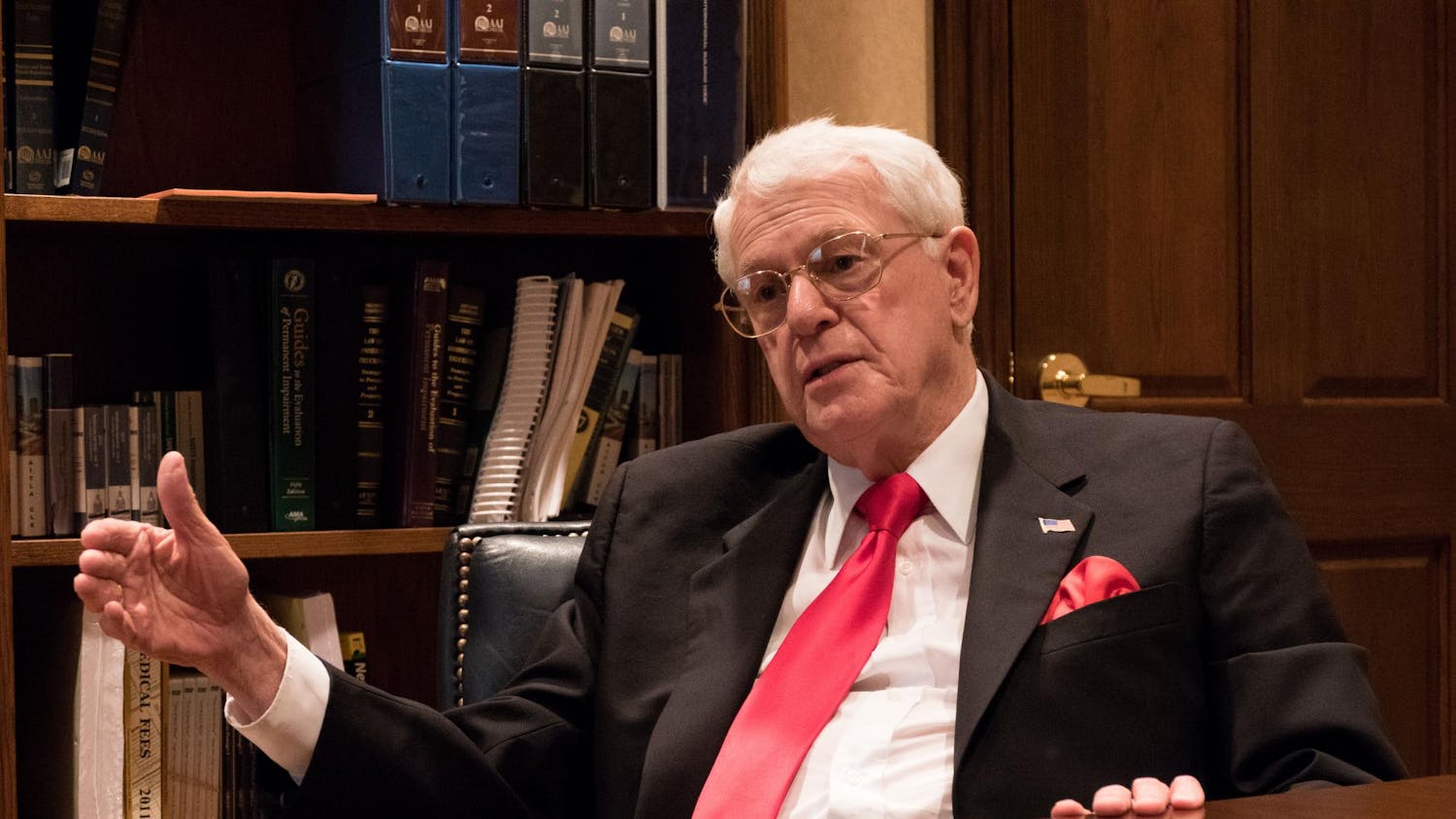

Imagine a smoky nightclub, shoulder to shoulder with slicksters, all feeling the groove of the music. Suddenly the fire alarm blares. In the midst of the confusion, people glance around and wonder, "Is it real?" A sudden pulse of anxiety grips the crowd, as everyone thinks the same thing: must get out.\nCrowd emergencies are incredibly rare, but as the recent nightclub fires in Rhode Island and Chicago indicate, they do happen. Under the best circumstances of a fire, everyone gets out of the building, and no one is hurt. Under the worst, some people are trapped or trampled by a panicked mob. \nJerome Chertkoff, IU emeritus professor of psychology, has spent 10 years studying the factors that make the difference between a successful and a tragic emergency evacuation. He has studied evacuations including airplanes, burning buildings and in his most recent study, passenger ships.\nChertkoff said awareness is the key from the individual perspective. In addition to making sure that a hotel or nightclub building is safe, people need to know how to get out, particularly if it's a complicated structure. \n"Pay as much attention as you can to the exits, not just the one you came in but other ones," he said. "There's a very strong tendency for people to know only one way out -- the way they came in -- and to use that."\nNine additional factors are important in land-based emergency evacuations, according to Chertkoff and colleague Russell Kushigian in their book, Don't Panic: The Psychology of Emergency Egress and Ingress. A structure needs to have enough exits of sufficient size. Managers need to have emergency training, control crowd size, manage crowd density and limit congestion beyond exits. Additional factors that affect a group in this situation include leader influence, perceived time available and perceived danger. \nAt the IU Auditorium, detailed emergency planning addresses many of these potential concerns. House Manager Jon Larkin said all employees and ushers receive personal training, and each event has emergency checklists and guidelines.\n"Ushers are trained for evacuation before every event by their managers," he said. "Each usher is given an emergency location where they are to report no later than one minute after the alarm sounds."\nChertkoff studies the social psychology of evacuations through a combination of simplified laboratory experiments and case studies of actual evacuations. In the laboratory, he and his colleagues have set up experiments with three to seven people who have decisions to make about whether to exit or whether to allow someone else to exit.\nMost recently, he has investigated case studies of passenger ships including unsuccessful examples like the Titanic in 1912 and the Lusitania in 1915, as well as successful examples like the Andrea Doria in 1956. Ship evacuations in port or near other ships are often similar to land-based evacuations, but in other cases, once survivors get off a ship, they face other factors that determine their survival.\nIn a paper that he will be presenting at the Second International Conference in Pedestrian and Evacuation Dynamics in August, Chertkoff lists five additional factors that can affect the survival of individuals evacuated from passenger ships including the speed of sinking, weather, communication, arrival of rescuers and the survival capacity. Most of the successful ship evacuations studied showed none of these additional factors and less than five of the land-based factors. \nOne of the challenges in his work is getting reliable information, particularly about successful evacuations. Most information covers only the failed evacuations.\nThe years of research about emergency evacuation have given Chertkoff a different perspective when he enters new buildings. He particularly remembers going to eat at Montgomery Inn on the Ohio River in Cincinnati when he was there for a conference. \n"You come in up stairways, and then the receptionist took us to our table and we were wandering around," he said. "But I was paying close attention to where we had come from and where we were going. So I could easily have found my way back to the stairway if I'd had to."\nThe actual probability that any person at any one time will be in a building that catches on fire is incredibly small. But Chertkoff compares fire safety procedures to wearing a seatbelt in a car. \n"The probability of your getting in an accident or getting hurt without a seatbelt any one time you ride in a car is infinitesimally low," he said. "But over your whole lifetime, the likelihood that sometime you'll come across a structure that you're in being on fire is not as low as you might think"

Professors say 'Don't panic'

Rhode Island nightclub fire brings greater awareness

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe