When am I ever going to use this class in real life? \nAlmost every college student has asked this question at some point, when frustrated, when giving in to a nap in an early morning lecture, or when cramming for a final exam at 4 a.m.\nAlthough often a frustrating question to many instructors, some embrace the question of relevancy as a challenge to engage their students. Associate instructor Carla Shirley accepted this challenge when she designed a Sociology 101 course using traffic tickets to see if racial profiling was happening in Monroe County. \nBased on their analysis of traffic tickets from the year 2000, they observed a disparity in the number of tickets given to minorities versus whites. These initial results indicate that racial profiling may be occurring. Their complete report will be submitted to the Monroe County Racial Justice Task Force and released to the public this spring.\nShirley found out about the traffic ticket project in spring 2001 through the office of IU Community Outreach and Partnerships in Service-Learning. This office serves as a connection point between the University and the Bloomington community for course projects that are both educational and beneficial to the community. \nAttorney Guy Loftman had brought the traffic ticket study to the service-learning office. The idea for the study came from a legal client who felt she had been profiled for a traffic ticket. \n"One day I just walked down to the clerk's office, and they're all public records, and asked if I could see some of them," Loftman said. "And they gave me a big stack, and I just added up the numbers of blacks and the numbers of whites." Of the 50 to 100 tickets he looked at that day, he saw a "substantial disparity" based on race in the numbers of individuals being ticketed. \nA member of the Monroe County Racial Justice Task Force, Loftman was interested in a series of studies that would establish whether racial profiling was prevalent in the county. When Shirley heard about the project, she thought it would be an interesting opportunity for students to see the implications of racial issues "not just other places, but where they are and where they live." \nDuring summer of 2001, Shirley and Loftman discussed what kind of data they wanted to collect from the tickets and conducted a pilot study. Since the traffic ticket information is not stored on a computer, they were collecting all of the information from paper traffic tickets stored in boxes in the county clerk's office. In addition to basic information such as race, age and gender, they collected information on types of infractions, officer numbers, types of officer, times of day, makes and models of cars, and where the cars were registered.\nDuring the course in fall 2001, Shirley prepared her students to code the almost 17,000 paper tickets, taking the students to the clerk's office in shifts to train them and then training them to enter the data in a computer database. \nShe also faced the challenge of clearing up ambiguities in the data. The race category was difficult because local law enforcement has not standardized how they label races on tickets. \n"There would be things like a 'C.' Presumably it's Caucasian, but it could be Chinese, Cuban, Chilean," Shirley said. "'A' could be Asian; it could be African-American." \nShe confirmed their assumptions with the Bloomington Police Department chief and the Monroe County Sheriff, but it became one example of how a simple variable could become a "coding nightmare." \nJoining the students taking the class for class credit, six advanced students applied to take the course for 300-level credit. These advanced students, including senior Samantha Barbera, took on additional responsibilities for data analysis, but each student was responsible for coding data from approximately 600 paper tickets. Barbera estimates that during a four week period she spent three days a week, and at least three hours per sitting, coding her share of the traffic tickets. \nBarbera and the other advanced students ran preliminary data analyses and presented their preliminary findings in December 2001. Barbera, senior James Austin and senior Glenn Conn also continued to work with Shirley last summer to check for errors and analyze additional variables. \nBarbera remembers her colleagues' excitement about the results of their work. By comparison, she said other courses "don't hold as much meaning because it's not real life and it doesn't affect you right then and there and you're not a personal part of its discovery."\nSociology Department Chair Rob Robinson was impressed by the students' final presentation.\n"You could just tell that there was tremendous enthusiasm for having done this kind of project that went way beyond what I think individual students would have been capable of doing," he said.\nShirley and Loftman think this study could allow law enforcement officers to see patterns that they otherwise might not have noticed. Shirley also said she thinks this work could be a model for other researchers who might be interested in taking on a racial profiling project.\nThe racial profiling project is just one example of a project that Shirley has worked on that connects race and ethnicity to communities she cares about. She continues to study "whiteness" in rural Mississippi. She also taught a course in summer of 2001 that studied race relations on the Bloomington campus. \nAlthough the racial profiling project involved countless additional hours for Shirley, it reaffirmed her long-time commitment to community-based research. \n"I really learned also how the University, how academia can be a very positive force in the community ... in terms of local concerns and trying to do studies and make change," she said.\nIn addition, this course has changed the career goals of at least one of the students. Barbera has decided to go to graduate school in sociology and hopes to see more courses like this one because she doesn't see a point in knowing "what all the wrongs in the world are if you don't know how to make them right"

Sociology project researches race relations

Get stories like this in your inbox

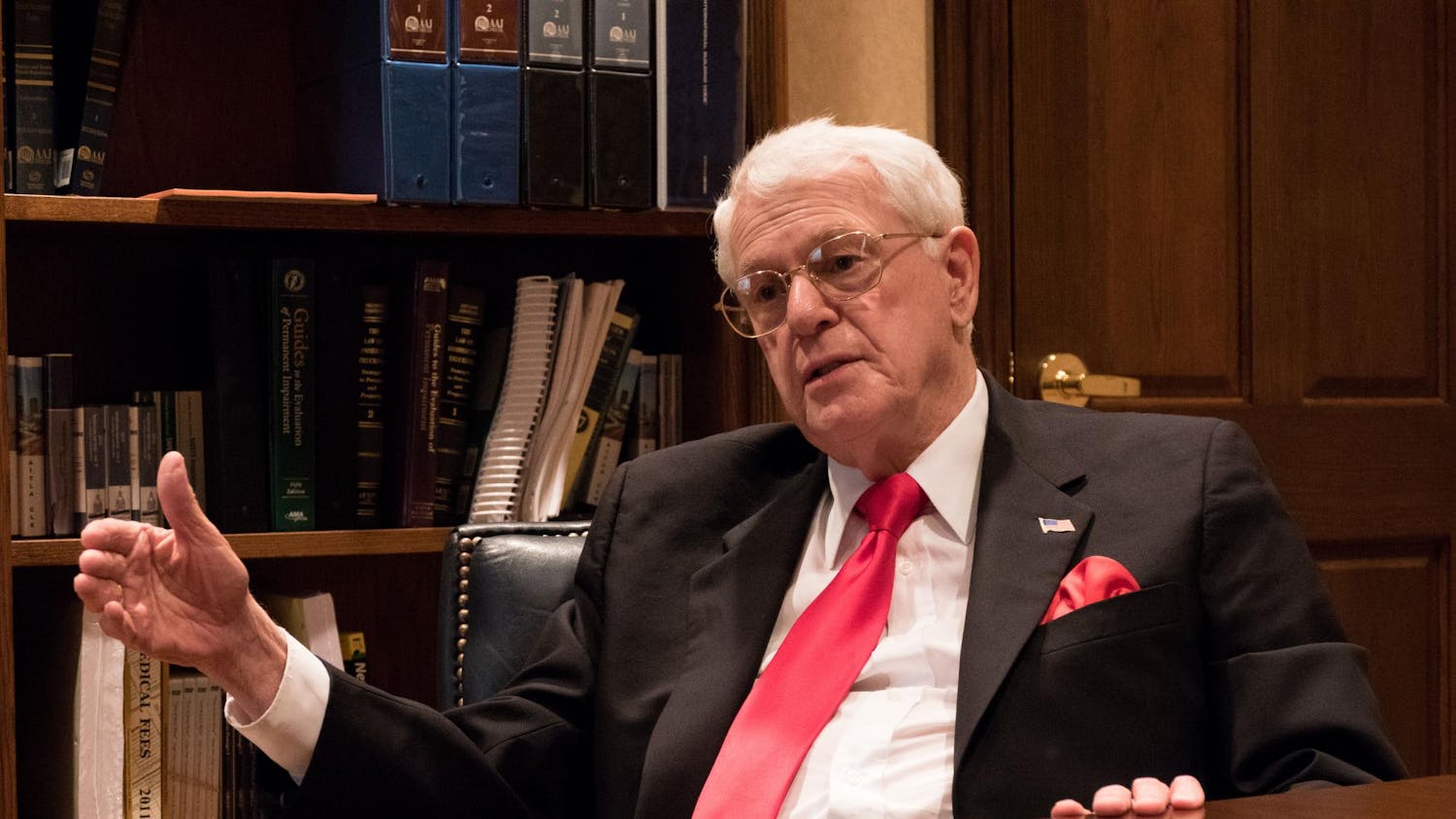

Subscribe