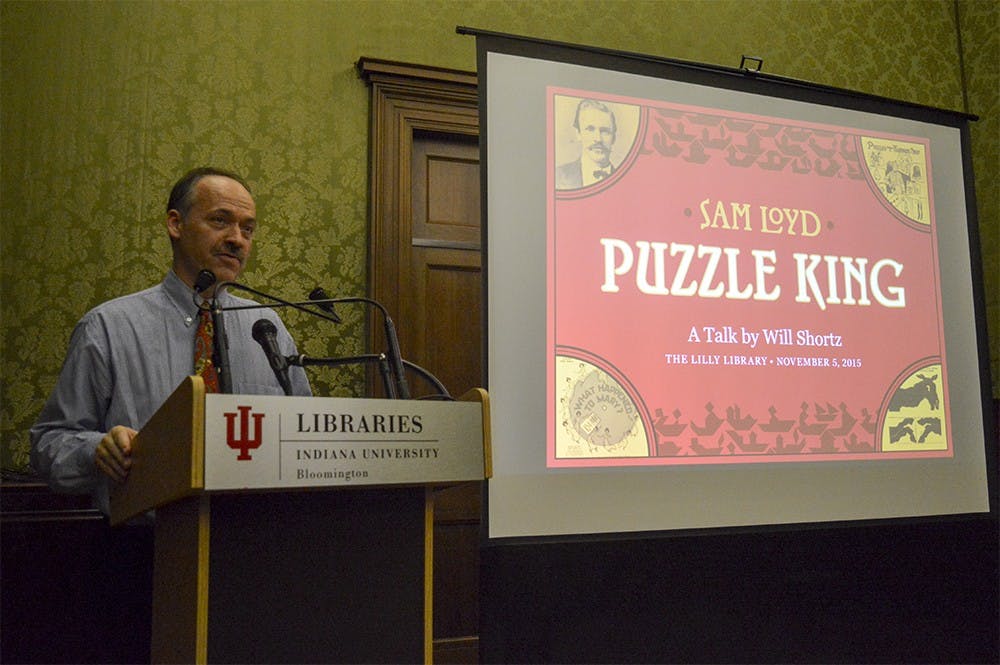

At “Sam Loyd: Puzzle King,” IU alumnus and puzzle-maker Will Shortz explained what makes Loyd’s puzzles great. At first they seem impossible, but with a clever twist or trick they become obvious, Shortz said.

Loyd, born in 1841, created mathematical and logic puzzles for newspapers and tradecards.

Loyd’s puzzles were usually visual — several involve moving three cards with pictures so a certain shape, such as a horse, appears.

An exhibit at Lilly Library presents many of Loyd’s creations, such as the original newspaper pages in which they appeared and wooden or cardstock versions of physical puzzles. Many of the objects on display came from Shortz’s personal collection.

Shortz edits crosswords for the New York Times and is the host on National Public Radio’s Sunday Puzzle.

“More than anything else, it was Sam Loyd who made me want to pursue a career in puzzles,” Shortz said.

At Thursday’s talk, Shortz said when he first read an article about Loyd, he thought, “I would like to be like that guy.”

Becoming like Loyd required Shortz to solve a seemingly impossible problem of his own — how to make a living through puzzles.

“Having a career in puzzles has always been my life’s dream,” Shortz said. “In the eighth grade, I wrote a paper on what I wanted to do with my life, and it was to be a professional puzzle-maker.”

When he came to IU, Shortz only joked about studying puzzles, but then he discovered the Independent Major Program.

Unsure he wanted to create his own major, he went to see an IMP counselor, and in that first meeting she made it sound like it would be difficult to create the enigmatology major.

“I remember coming out of the office determined that this was what I wanted to do,” Shortz said.

He took classes from professors in linguistics, English, mathematics and journalism.

At IU, Shortz was a member of a fraternity. He said he was “semi-cool.” If other students knew what he studied, Shortz said they generally thought studying enigmatology was interesting. He said he remembers one conversation, however, in which a fellow student said they thought Shortz was studying entomology, the study of insects, for most of the conversation.

Even during his senior year, Shortz did not wholly think it was possible to make a career in puzzles. He said he planned to study law, go into practice for 10 years and then retire and make puzzles.

The spring of his senior year in 1974, he wrote the puzzle companies to request a summer job. One magazine responded and hired him to edit crosswords.

“Here I was, as an editor — I was making money,” Shortz said. “That let me see how I could have a career making puzzles as an editor.”

He started law school at the University of Virginia but wrote his parents in the spring of his first year to say he had decided to drop out to go into puzzles.

“My mom wrote me a long letter why that was a bad idea,” Shortz said. He finished law school.

Instead of sitting for the Bar exam, he found a job with Penny Press, a crossword magazine company.

In 1993, he became crossword editor at the New York Times, and in 1987, NPR invited him to become puzzlemaster on Weekend Edition.

Every week, he challenges the country with puzzles such as this one, from NPR’s Weekend Edition on April 5, 2015:

“Given a standard calculator with room for 10 digits, what is the largest whole number you can register on it?”

The answer isn’t 9,999,999,999. Though it seems impossible at first, with a twist and a trick, the answer is obvious.

“If you key in 709,009 and turn the calculator upside down, it will read ‘GOOGOL,” a one with a hundred zeros after it.