Teddy bears and cuckoo clocks line the walls of Gudrun Ferguson’s small living room, where the 73-year-old blonde-haired German immigrant says she spends most of her days alone, knitting blankets or working on crossword puzzles.

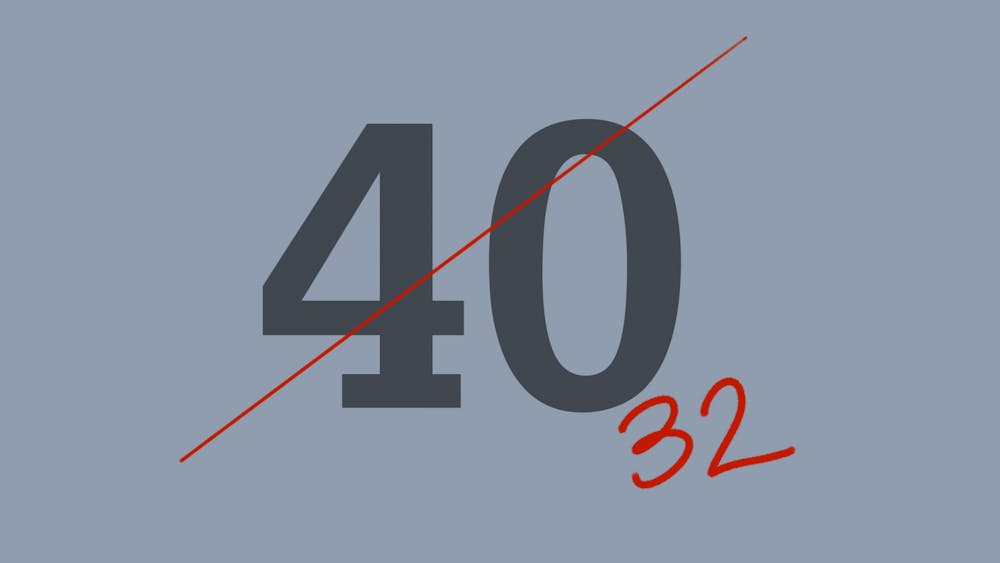

Gudrun is one of the more than 4,590,000 people older than the age of 65 nationwide who are considered to be living below the federal poverty line. That line is drawn at $11,880 annual income, or just $990 a month for a one person household.

Gudrun receives $695 a month in social security benefits. After she pays $457 for her rent, $90 for her cable and telephone bills, and the rest for car insurance, life insurance and utilities she only has $15 left.

Although she uses her small savings account to compensate for the expenses that social security cannot cover, Gudrun is still unable to pay for everything, including air conditioning, medications and car repairs, that she needs to live comfortably.

As the baby boomers age and the cost of healthcare and living expenses rise, the number of elderly people who cannot pay for basic necessities is quickly increasing both in Monroe County and the United States.

According to United States Census Bureau data, the number of individuals more than 65 years old living below the official poverty line is up by more than a million since 2009.

Seniors are considered to be an at-risk population. Seniors are one of the most vulnerable groups of people in terms of food security and housing, according to Tim Clougher, the assistant director of Monroe Community Kitchen. Elderly people face several challenges making ends meet and accessing the social services that can help them due to mobility, health problems or social isolation.

Even those who have jobs can slip into the grips of poverty. Steven Murphy, a 62-year-old panhandler, was evicted from his apartment last October after he wasn’t able to pay rent for two months in a row.

His wife, Rosie, fell and broke her leg a few months before their eviction. After she was hospitalized, she was forced to quit working in order to heal properly, which meant the couple had half of the income they depended on.

Steven called friends and family to borrow the money he needed to pay their rent but couldn’t get the money in time.

“I got the money to pay, and just as I was walking up with it the sheriff came up and served the eviction notice,” he said. He disputed the eviction in court but lost.

“Some of them tell you ‘get a job,’ but I got a job so that don’t help much,” he said. He works part time at a Kroger on the west side of town and has to take the bus each day to get there.

When he is not working at Kroger, Murphy stands on Kirkwood Avenue and begs for money with a cardboard sign. He said he hopes to save enough money so he and his wife can get their own place again.

Despite the rise in seniors in need, organizations like the Area 10 Agency on Aging, which provides services such as emergency health care and housing assistance, have not been able to compensate for the quick increase in the number of people who need their services. Some clients are even wait-listed after requesting assistance.

In addition, not having the physical ability to access the organizations means people are not always able to eat, even when they need food.

“What it ends up meaning is that they just skip meals,” said Stephanie Solomon, the director of education and outreach at Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard food pantry.

Some also simply don’t know how to access or contact those services.

For many seniors the best way to reach out to the services is through word of mouth or paper advertisements because many seniors do not have computers or cannot access the internet to find the services which they need.

“Although phone books are becoming obsolete, for some people using the phone book is all they know,” Tim Clougher said.

Many people also see their pension plans reduced when the factories and companies that they worked for move out of the area or downsize.

“People had retirement plans with the companies, but once they left, their retirement plans did too,” Clougher said. Companies like RCA, Otis Elevator and Thompson were major employers in the area and provided large retirement packages to many of their workers until they moved away.

Just as the Murphy couple lost its housing because Rosie could not work, Gudrun Ferguson sacrifices health care to pay for rent and food.

After being laid off from two long-term jobs and being mistreated by her manager at Goodwill, Ferguson decided to retire last year.

Now, she has lived with chronic pain for the past two years because she says that the necessary pain medications would cost her $90 a month, even with insurance.

She visited a pain management center in 2014 to seek treatment for the back problems she had as a result of her late husband’s physical abuse. She was hospitalized many times over the course of their marriage for two broken ribs and a punctured lung, among other injuries, and was never able to reach a full recovery.

However, her pain only got worse after the doctor botched an injection in her sciatic nerve. In addition to the back pain, she now feels pain in her leg every day, which she said was a result of the injection.

“The doctor came in and just did it without saying anything,” Gudrun said. “I thought it was a shot for the pain.”

She no longer wants to pursue pain management because she is fearful of another bad experience in addition to the extra expenses.

Now instead of paying for treatment, Gudrun said she prays the pain will not get worse.

The fillings and tooth extraction she needs were also put on hold because she doesn’t have dental insurance and doesn’t have the money to pay the $1500 out of pocket.

“I’m 73. I’m doing just fine. I don’t need to pay no partial. I may die next week, who knows. I’m not worried about dying,” she said.

The repairs her car needs would also cost her $120, which would put her over her budget. She used to go to church every Sunday, but now she only goes on days when it isn’t raining out because she has to walk there and cannot afford to fix her car.

“When you get to that level of limited resources, housing, food, medical care and all of those basic things that we all need to live and thrive become hard to access,” Solomon said. “Seniors are a population that is incredibly under-served.”