A new study by IU psychologists has found that distracted caregivers may raise children with shorter attention spans.

The psychologists’ research, published online in the journal Current Biology, is the first to show connections between how long a caregiver focuses their eyes on an object and how long an infant focuses on that same object, according to an IU press release.

Chen Yu, who led the study supported by the National Institutes of Health, is a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. He said in the release children’s ability to sustain attention is known to be a strong indicator for success in language acquisition, problem solving and other developmental milestones.

“Caregivers who seem distracted or whose eyes wander a lot while children play appear to negatively impact infants’ burgeoning attention spans during a key stage of development,” Yu said in the release.

Linda Smith, a distinguished professor and Chancellor’s Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences, co-authored the paper.

“Historically, psychologists regarded attention as a property of individual development,” Smith said. “Our study is one of the first to consider attention as impacted by social interaction. It really appears to be an activity performed by two social partners since our study shows one individual’s attention significantly influence another’s.”

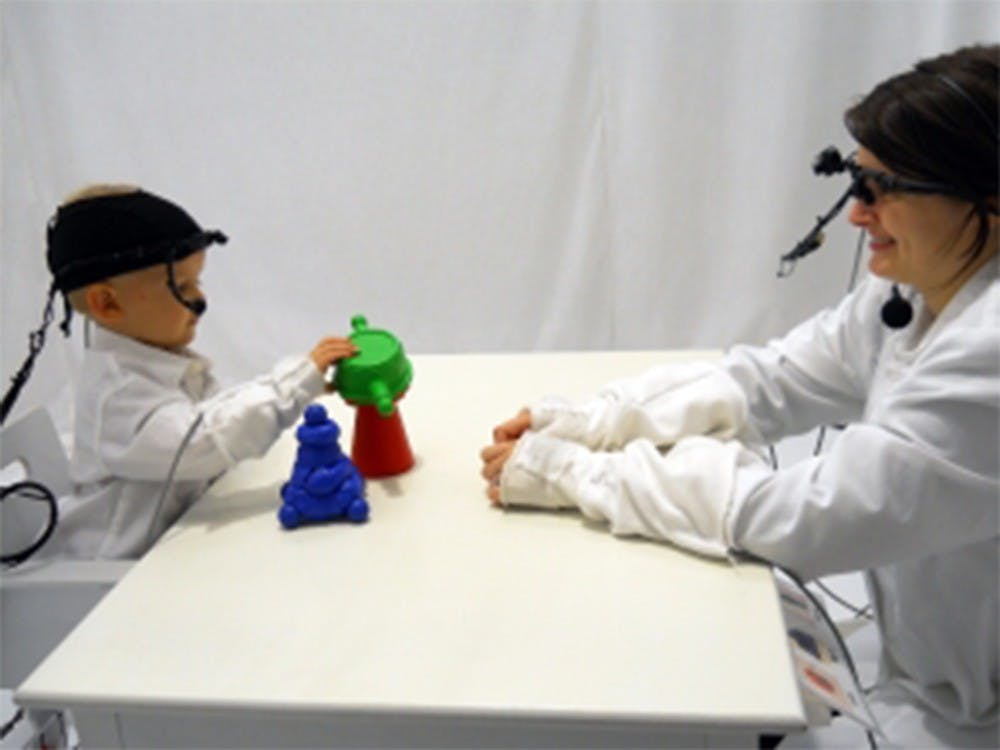

In the study, caregivers and infants both wore head-mounted cameras to provide a first-person point of view of parents and children playing in an environment created to resemble a home or day care play session.

Unlike similar studies, this technology allowed caregivers and children to play with physical toys, rather than objects manipulated on screen, according to the release.

Yu said in the release parents either allowed infants to direct the course of play or attempted to forcefully guide the infants’ interest in particular toys. The caregivers were given no instructions prior to play so researchers could gain an unfiltered understanding of the caregivers’ and infants’ interactions.

“A lot of the parents were really trying too hard,” Yu said in the release. “They were trying to show off their parenting skills, holding out toys for their kids and naming the object. But when you watch the camera footage, you can actually see the children’s eyes wandering to the ceilings or over their parents’ shoulders — they’re not paying attention at all.”

The study found caregivers who “let the child lead” were the most successful at keeping the infant’s attention, according to the release. These caregivers named toys and encouraged the infant to play with the objects after the child expressed interest in the toy.

“The responsive parents were sensitive to their children’s interests and the supported their attention,” Yu said in the release. “We found they didn’t even really need to try to redirect where the children were looking.”

When children and caregivers paid attention to the same object for more than 3.6 seconds, the child’s attention stayed with that object for 2.3 seconds longer on average even when a caregiver’s attention changed, according to the release. This time adds up to be nearly four times more than that of infants whose caregiver’s attention changed quickly.

Yu said these times, although initially appearing small, are magnified when considered over an entire play session or throughout months of daily interaction during a critical development stage. Other studies in children ages 1 through those in grade school have found conclusions that longer attention spans at an early age can predict future achievement, according to the release.

Sam Wass, a research scientist at the University of Cambridge whose commentary has been published in Current Biology, said Yu and Smith’s work has been hugely influential.

“Showing that what a parent pays attention to minute by minute and second by second actually influences what a child is paying attention to may seem intuitive, but social influences on attention are potentially very important and ignore by most scientists,” Wass said in his release.

The shortest attention spans in the study were found in a third group where caregivers exhibited very low engagement while playing with the children, typically sitting back, diverting attention and not playing along.

“When you’ve got a someone who isn’t responsive to a child’s behavior, it could be a real red flag for future problems,” Yu said in the release.

Carley Lanich