We are a nation of symbols.

The horrific tragedy that transpired in Charleston, South Carolina, late last week has sparked a handful of vociferous national conversations, as well it should. Rather than tackling the pervasive, enduring epidemic of racism in this country, the controversy has chosen the Confederate flag as both the litmus test for progressiveness and the battleground on which the victims may be avenged.

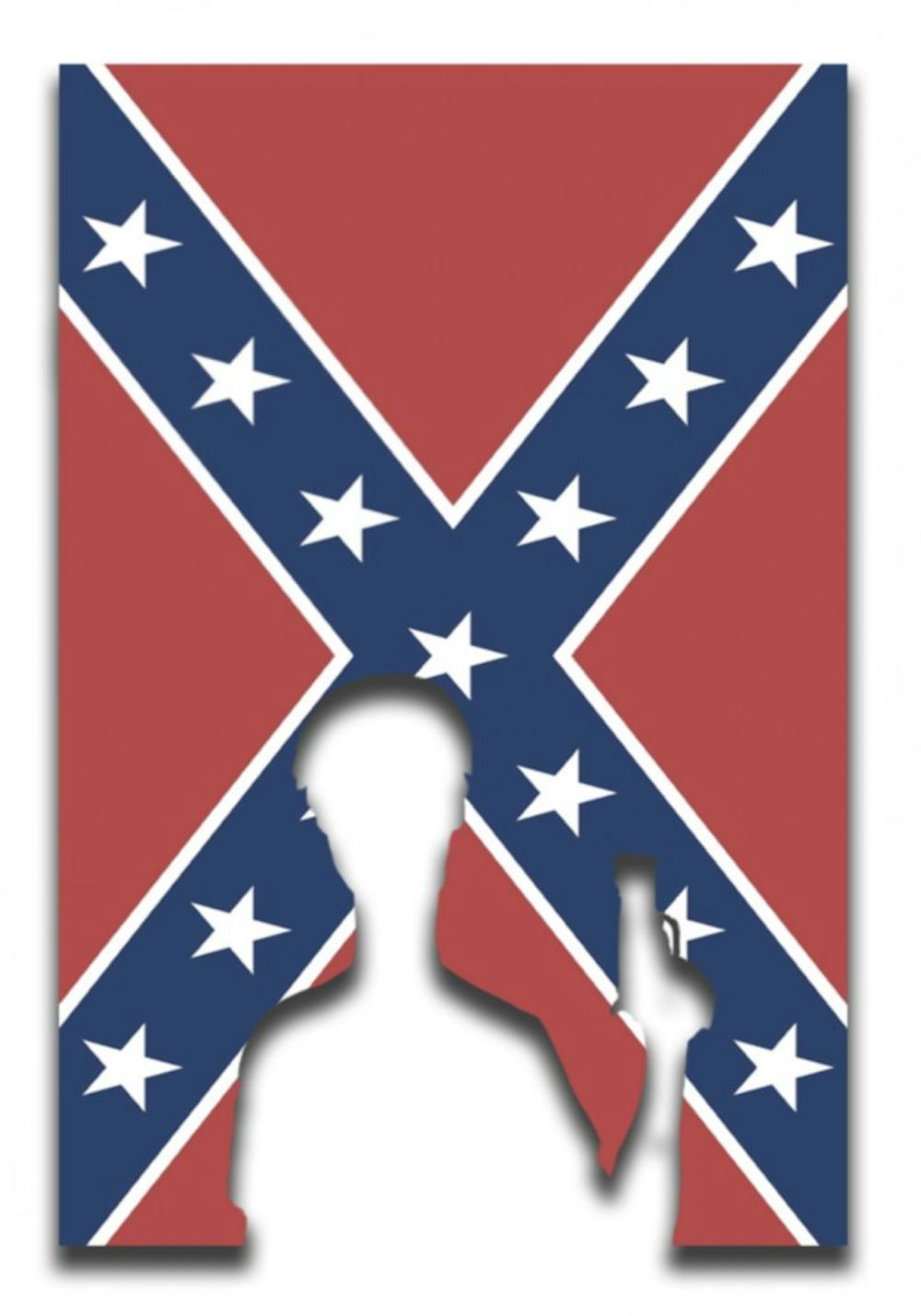

As soon as photos of Dylann Roof holding a Confederate flag began to surface, the rhetoric of injustice dissolved and the rhetoric of combat took its place. After all, this historically fraught icon of oppression and violence is much easier to fight than the actual sentiments thereof still seething in our national subconscious, as evasive and clouded as they are volatile.

Americans are under the erroneous impression that scapegoating the symbol of a shameful past will in fact purge the psychological and perspectival vestiges of that past from our hearts and minds. We have mistakenly imbued the stars and bars with all of our collective guilt and sorrow and are now in the process of offering it up as a sort of transubstantiated vessel of salvation — one which, once eliminated, will take our sins ?with it.

We cannot expect a symbol of cruelty and hatred to become a vehicle of redemption. And yet, we are no longer talking about Charleston’s grief. We are talking about its flag.

A similar trend has emerged within the movement to procure social and legal equality for members of the LGBT community. Or, rather, the movement to procure marriage equality. While the nation celebrates Pride and awaits the Supreme Court ruling on four marriage equality cases, demands for equal federal marital recognition have amplified.

But the conversation too few are having is one highlighting the myriad ways in which LGBT Americans suffer from injustice, a list receiving the right to marry won’t begin to address.

Among the LGBT community, basic safety remains a huge concern. Fewer than a third of the states include sexual orientation and gender identity in their hate crime laws. Homophobic and transphobic attacks comprise over 20 percent of hate crimes, and half of transgender people have experienced sexual violence. Yes, the right to marry is one which should be extended to all citizens without question. But putting all of our proverbial activism eggs in the marriage basket is a move which lacks ?intersectionality. Beyond the federal financial benefits marriage offers, it is, on the most basic level, a symbol.

What about the right to exist beyond the ever-present shadow of threat? What about the right to live as a human rather than the legally vulnerable target of hatred and violence? Who will protect citizens who don’t seek marriage but wish to simply walk down the street without fear?

Symbols are powerful, compelling, evocative and useful. They unite us, divide us, inspire us and horrify us.

All humans deserve equal marital rights, and the Confederate flag cannot disappear quickly enough.But we cannot let the shorthand of an idea become the idea itself. We cannot accept the manipulation of a totem as sufficient in the fight to transform the sentiment. They are not the accessories of contentment; rather, the loci of initiative.

sbkissel@indiana.edu