George Taliaferro remembers the first night he came to IU. He called his father and cried afterward.

Taliaferro, now 87-years-old, came to Bloomington in 1945 to get an education and play football. But the 18-year-old African American was shocked by how segregated IU was at the time.

He figured a community based around learning and knowledge wouldn’t do something so disgustingly traditional as to segregate.

But Bloomington was segregated.

Taliaferro couldn’t live in the dorms. He couldn’t go to certain shows at the movie theater. He couldn’t go swimming at the pool.

So on that first night he called his father and told him he didn’t want to come to IU. He wanted to come back to Gary, Ind., and live in his community of integration. His neighborhood wasn’t integrated between whites and blacks, but between blacks and Europeans from Germany, Italy, Yugoslavia and other countries.

“I thought my father would say to me, ‘Son, I agree with you. If they don’t want to treat you like every other human being, you shouldn’t go to school there,’” Taliaferro said, now sitting in his kitchen.

He lives on the south side of Bloomington and has lived 42 years in the city that gave him such a bad first impression.

But on that phone call on his first night, he didn’t receive compassion from his father.

George still remembers the conversation.

“Son, can I ask you one question?” George’s father said.

“Yes sir,” George responded.

“Is there another reason you are at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana?” George’s father said.

George’s father hung up the phone.

“I lay there with tears coming out of my eyes,” George said, recounting the memory.

***

It wasn’t until later that night, unable to shake the feeling of why his father hadn’t understood him, that George realized what his father meant.

“I am here to be educated,” George realized.

To George’s father, receiving an education didn’t mean you got along with everybody. It didn’t mean you just went to class, studied the books and took a test.

An education for the Taliaferro family meant learning about the real world, what real people think and how they act. Especially how the real world acted toward black people. A person shouldn’t stay in their comfort zone their whole life, George said.

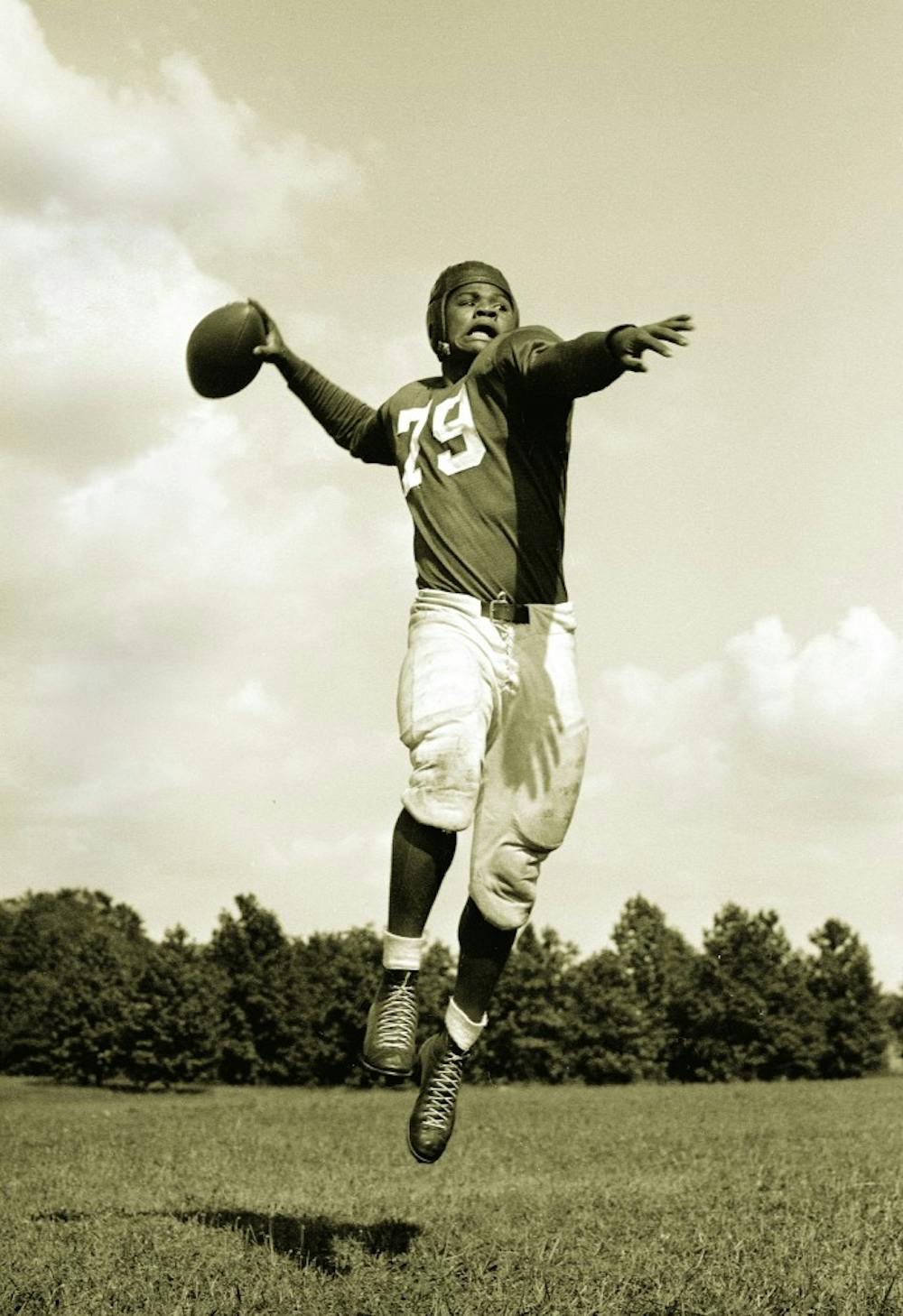

During his time at IU, Taliaferro was a three-time All-American and helped IU to its first and only undefeated Big Ten season.

Now, his picture hangs from the rafters outside of Memorial Stadium with other IU football legends.

Taliaferro was certainly not comfortable when he first arrived at IU, even though he went on to achieve greatness.

Taliaferro, who wasn’t allowed to stay in the same dorms as his white peers, left IU as one of the most important figures in not only IU athletics history, but in civil rights history.

He became the first African American to be drafted into the National Football League, selected in the 13th round by the Chicago Bears.

While black players had been playing in the NFL before Taliaferro, none had been drafted into the NFL. Taliaferro opted not to play in the NFL immediately, instead deciding to play for the Los Angeles Dons of the All-American Football Conference first out of college.

After just a season with the Dons, Taliaferro went on to play in the NFL for six years, making three pro bowls in his career. Taliaferro played for the New York Yanks, Dallas Texans, Baltimore Colts and Philadelphia Eagles.

But still, when he first came to IU, he was shocked by how he was treated as a second-class citizen.

Earlier this month, America celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The historic act outlawed discrimination of a person based on their religion, sex, national origin or race.

But even today, Taliaferro sees racism all around him. He doesn’t believe black people will be treated as equals any time soon.

“I can’t tell you how discouraged I am when I see entire states who are looking down on giving all human beings equal education,” Taliaferro said. “We’re nowhere near the end. We’re nowhere near.”

***

Taliaferro gets up from his seat at the kitchen table, eager to pull out a piece of memorabilia he’s kept for more than 50 years.

“I got something I want to show you,” he said.

Taliaferro grabs a manila folder, which is starting to tear because of all the papers he keeps inside. George doesn’t use the computer, or as he calls it, “that son-of-a-bitch.” He keeps newspapers clippings of articles he finds interesting.

Some of the clippings include a front-page story the IDS wrote on him and his wife, Viola. Another clipping from just a few weeks ago is from the Herald-Times announcing the addition of the IU Student-Athlete Bill of Rights.

He opens the folder and looks through the papers.

“Ah, here it is,” he said, pulling out a white metal sign. With a white background and blue letters, the sign is roughly the size of a street sign.

And in the bold blue letters the sign reads, “COLORED.”

“I show this everywhere I go,” Taliaferro said, holding the sign like a trophy.

After he came back from serving overseas in the United States military during World War II, Taliaferro went to the Princess Theatre — an old theater in Bloomington which has since gone out of business. The theater was notorious for segregation, Taliaferro said. There was an area for blacks and an area for whites.

He went to the theater that day with a tool.

A screwdriver.

“I said, ‘I’m going to take that sign down,’” Taliaferro said. “‘And that sign ain’t gonna work no more.’”

George Taliaferro has always pioneered for racial equality. He says America has made gains during his life, but he is pessimistic as to whether this nation can ever reach true equality.

“Not the United States,” Taliaferro said. “Because we as a country do not wish to give credit to African Americans for our participation in developing this country.”

“Why then, would something happen suddenly in this country to bring white people to recognize that we, too, share the national anthem?”