The shop is nearly silent.

It’s Friday afternoon, and people walk up and down the sidewalk outside, popping in and out of other businesses on the Courthouse Square. Inside the bookstore, Janis Starcs is alone. He crouches near the bottom shelf of the political science section at the back of the shop.

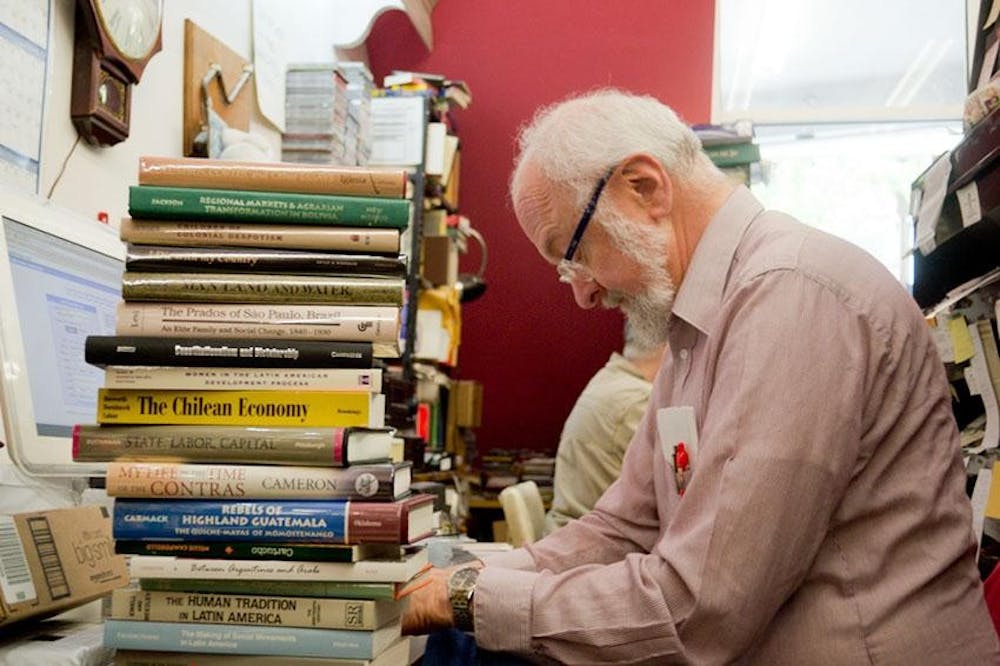

Starcs, 69, is the co-owner of Caveat Emptor, one of three booksellers on the Square, but the only store in Bloomington that specializes in rare and used books. It’s been open since the early 1970s.

He rises, carrying a stack of four books he’s going to re-price through the maze of tall, wooden shelves. He makes his way back to the front of the store where an old Macintosh laptop sits open at a counter amid stacks of dusty books, CDs and discarded copies of The New York Times.

Caveat Emptor started selling books online last fall, but both the store and its owner continue to exist in a remarkably non-digital world.

But for better or worse, from between the bookshelves of what he calls his “little corner of Western civilization,” Starcs is simultaneously immersed in and resistant to the digital revolution. He, like booksellers across the country, has seen a drop in the number of people browsing the volumes in his shop, yet he has only slowly and minimally given in to the attractions of a modern, digitally connected society.

“There are fewer and fewer places like this, because the Internet is really killing their business,” Starcs said. “We’re really the only full-line used bookstore in town now.”

There used to be two local stores with which Caveat Emptor competed, he said, but they both closed at about the same time more than 10 years ago.

“It’s really hard to compete against people operating out of garages, attics, basements,” he said. “People like that are hard to compete against.”

STARCS’ CREATION

Sales at Caveat Emptor revolve around books and CDs, but the place itself is like a window into Starcs’ head.

Editorial cartoons and newspaper clippings are taped to the ends of the bookshelves, reflecting Starcs’ personal opinions. He’s a Republican precinct committeeman for Perry 30 on the south side.

He follows politics every day in The New York Times and Real Clear Politics.

“That’s my only spectator sport, as it happens,” he said. “You have to keep up with what people are reading and thinking.”

Throughout the store Starcs’ preferences shine through.

Because Caveat Emptor only sells books that are both rare and used, Starcs and his employees have room to be selective in what they choose to buy and sell.

The books that fill his store’s shelves are the kind of books that can’t be found anywhere else. He has first editions, complete collections of authors’ works and historical commentary on topics ranging from politics to science.

He said he’s long had a passion for books.

They helped him understand the American culture he was thrown into after his family fled World War II-torn Eastern Europe in 1944.

Today, a faded, red-and-white Latvian flag hangs vertically above the front door to Caveat Emptor. It’s a symbol of his heritage and what his family left behind when he was 7 years old.

Both of Starcs’ parents had been scientists in Latvia before they moved to the United States, and they passed on their scientific curiosity to their son.

“I was just generally trying to understand the world I was thrown into,” Starcs said. “I learned an awful lot in library stacks.”

Starcs even credits books for why he never finished his undergraduate history degree from IU.

“One of the reasons for those incompletes was I was chasing things around in the stacks.”

CHANGING CLIENTELE

Usually, people roam the aisles of Caveat Emptor, looking at titles, but many don’t buy anything.

“We get quite a few browsers,” Starcs said. “They’re looking for a specific book or some certain kind of book, and we don’t happen to be well-stocked in that area that day.”

On a normal day, there could be anywhere from 10 to 25 paying customers, Starcs said. On a busy Saturday, that number can hit 30 or 40. He’s even seen 50-customer days. But there are weekday mornings when, in the first hour of business, only one person enters the shop.

“We’re kind of hard-pressed to keep it in the black,” he said.

As the owner of a more than 40-year-old independent bookstore, Starcs has watched the number of customers diminish and his industry change. Even in college towns like Bloomington, books’ desirability has dipped dramatically in the past 20 to 30 years, he said.

There was a time when students worked to build personal libraries in their academic fields, poring over shelves of volumes in stores like Caveat Emptor, but that’s all changed.

“Students kept getting less and less interested in owning books. Undergraduates became less and less interested in building academic libraries,” Starcs said. “Books are becoming less sources of information and more objects to collect or for some talismanic value for the owner.”

Caveat Emptor’s business didn’t disappear overnight.

“It’s been a very gradual process, almost imperceptible, really,” Starcs said. “These long-term trends take a while to manifest themselves and get noticed.”

Starcs also said he has seen a reluctance to study the history of academic disciplines.

But now, he said, many students — undergraduates especially — disregard historical texts. There are exceptions. Caveat Emptor still stocks and sells copies of the Federalist Papers and Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations,” works that are more often used in undergraduate courses.

“All this stuff has a history behind it,” he said. “There are still people around who want all this stuff. I’m here for those people.”

Increasingly, though, these people are not the students that once supported Caveat Emptor and its predecessor — an academic and pop culture store Starcs owned and operated with friends shortly after he left the University. Every customer is different.

Some are visiting academics and speakers, like New York Times columnist David Brooks, who spent $100 at the store when he came to town to speak in November 2011.

Others are an older clientele, like Brandt Steele, a retired Depauw University faculty member who makes the trip to Caveat Emptor whenever he drives in from Greencastle, Ind., to visit his daughter in Bloomington.

There are still T-shirt-and-shorts-wearing college students who often search the shelves and leave with one or two paperback books that pique their interest.

But students can now find information they’re looking for in new ways that were not available even two decades ago.

Twenty years ago, the concept of an e-book would’ve been impossible to execute on a large scale, yet in 2010, 114 million e-books were sold, according to the Association of American Publishers.

But Caveat Emptor still has an audience. Starcs said he thinks most people would prefer to hold a book in their hands, and some of those people have started to find him.

“I’ve been noticing more customers who have discovered used bookstores for the first time,” Starcs said.

Independent stores with their owners’ personal flair have broader, more constant collections of books as compared to big chain bookstores, Starcs said. At Barnes and Noble, if a book isn’t selling well, it’s taken off the shelf, whereas Starcs can build a collection on one topic throughout a long period of time and then sell all related books to one buyer when someone finds out the store has what he or she is looking for.

“This is darn near the last survivor. There used to be four or five stores of this kind around Bloomington,” Steele said. “I don’t understand why.”

EMBRACING A DIGITAL FUTURE

The computer in Caveat Emptor is an old, white Mac laptop.

It sits on the desk near the front door. Starcs and employee John McGuigan use it to help them determine a book’s worth by researching how much it costs elsewhere and how many copies are in circulation. Databases detail what’s in stock and credit for those who’ve sold to the store.

Until recently, Caveat Emptor decidedly did not sell online.

“Browsing is a different experience,” Starcs said. “You can tell a lot more about what you’re buying in the store than online, when you can look in books and not just at an ISBN or a picture of the cover, if you’re lucky.”

But necessity prompted Starcs to build an online used bookstore on Alibris.com, a website that allows independent booksellers to move to the Web.

Starcs said the Web store has helped diminish a problem rare and used bookstores often have: “knowing you have a great collection in some field and just waiting for people to come along who are also interested.”

It expanded the store’s potential customers from those in Bloomington who are interested in used books to the global market.

“Maybe no one in Bloomington wants it, but maybe someone else wants it,” he said. “We were building up a collection of good books. People weren’t buying locally. You put a list online and suddenly everyone in the world can see it.”

Thus far, the online store has proven successful for the business, Starcs said.

On average, Caveat Emptor makes a sale online once per day. Some days there are four or five orders, but there are three- or four-day stretches when no one buys online.

“It’s not a primary source of income, but it’s a nice supplement to the normal flow of business,” Starcs said. “Walk-in is still the primary source of income. Walk-in sales are probably 90 to 95 percent.”

UNCERTAIN NEXT STEPS

People pass by outside in the bustle of Walnut Street mid-Friday afternoon. They have their smartphones out, and most won’t look at the used bookstore they pass.

Inside, Starcs goes about his business as usual. He carries books to and from the desk, verifying what they’re really worth.

He said there are usually more people in the store on Friday afternoons.

He’s not sure how much longer his store will be around, but that’s not because of financial difficulties. He’s 69, and at some point he’ll retire from the bookstore business.

Starcs reconsiders Caveat Emptor’s long-term viability every year, and he’s confident it will at least survive the next few. But he has no interest in changing what he does.

“It’ll depend upon how many people are interested in what we’re doing,” he said. “Most people, I think, are still used to holding a book in their hands.”

Local used and rare bookstore owner faces a digital future

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe